Researchers at MIT have achieved a significant step toward a single-dose HIV vaccine, demonstrating in mice that a combination of two established adjuvants dramatically boosts the immune response. The study, published in Science Translational Medicine, shows that pairing aluminum hydroxide (alum) with a saponin-based nanoparticle (SMNP) creates a sustained, highly diversified antibody response against HIV, potentially paving the way for one-time vaccinations against various infectious diseases.

The Problem with Existing Vaccines

Most vaccines rely on adjuvants to amplify the immune system’s reaction to an antigen – the substance triggering the immune response. While aluminum hydroxide is commonly used, it doesn’t always generate the robust, long-lasting immunity needed for diseases like HIV. The new approach tackles this issue by leveraging the strengths of two distinct adjuvants, creating a more effective synergy.

How the Combination Works

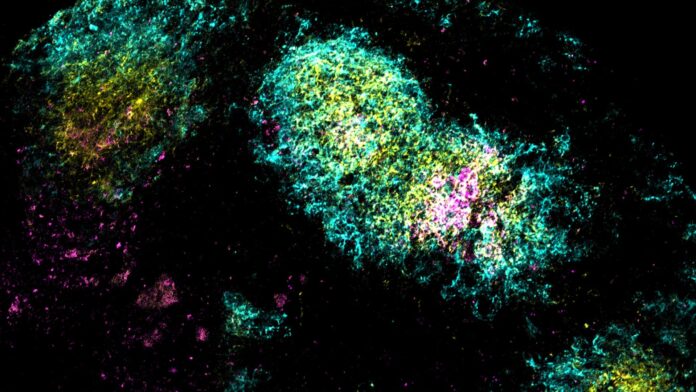

The MIT team anchored HIV proteins to aluminum particles alongside the SMNP adjuvant. This combination allowed the vaccine to accumulate in lymph nodes – critical sites for immune cell interaction – for up to four weeks. This prolonged exposure to the antigen provides B cells, the antibody-producing immune cells, with extended time to refine their response.

“As a result, the B cells that are cycling in the lymph nodes are constantly being exposed to the antigen over that time period, and they get the chance to refine their solution to the antigen,” explains J. Christopher Love, MIT chemical engineering professor.

The researchers found that this dual-adjuvant strategy increased the diversity of B cells and antibodies generated by two to three times compared to using either adjuvant alone. This diversity is essential for developing broadly neutralizing antibodies, which can recognize multiple strains of HIV – a critical hurdle in HIV vaccine development.

Broader Implications

This approach isn’t limited to HIV; the same principle could be applied to vaccines for other infectious diseases, including influenza and SARS-CoV-2. The combination of well-understood adjuvants offers a pragmatic path toward single-dose vaccines, reducing logistical challenges and improving global accessibility.

“What’s potentially powerful about this approach is that you can achieve long-term exposures based on a combination of adjuvants that are already reasonably well-understood, so it doesn’t require a different technology,” Love adds.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health and other institutions, underscoring its significance in the ongoing fight against infectious diseases. While further research and human trials are needed, this study represents a promising leap forward in vaccine technology.